In 2016, a core group formulated and published the most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of AF.7 These guidelines were the focus of their own session, starting with an overview and then a closer look at some of the significantly modified recommendations pertaining to the treatment of AF.

General Management and Gaps in Evidence

There are five domains of integrated AF management, and these interventions should lead to haemodynamic stability, cardiovascular risk reduction and stroke prevention, and provide improved life expectancy. Together, they should result in symptom improvement, and improved quality of life, autonomy and social functioning.

“The guidelines put a strong focus on integrated AF management,” said Prof Harry Crijns of Maastricht, the Netherlands. “It’s a top priority. That’s about patient involvement in multidisciplinary teams. It’s also cooperating in multidisciplinary chronic AF care teams when patients are simple, and working together in AF heart teams when patients need complex decisions.”

However, there are many gaps in the evidence, mostly with regard to antithrombotic or anticoagulation treatments, such as left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention, or anticoagulation in AF after intracerebral bleeds. These are mainly the result of the lack of patients needed to sufficiently power clinical trials.

Prof Crijns reviewed the results of several studies that help to address these gaps in the evidence, although they do not offer definitive guidance, and highlighted the need for further study. For example, more studies are needed to evaluate the impact of stopping anticoagulation after ablation in lower-risk patients, for instance in patients with heart failure due to tachycardiomyopathy, or with a mixed heart failure pattern (e.g. congestive heart failure, tachycardiomyopathy). Another example is the need for new studies in patients who have contraindications for anticoagulation, and especially also patients who have had an ischaemic stroke while on anticoagulant therapy, which is an important part of the Maastricht University patient population.

Concerning research into producing permanent transmural and longitudinal continuous lesions, researchers at Maastricht are studying a hybrid thoracoscopic surgical and transvenous catheter ablation approach. This pilot trial, called the Hybrid Versus Catheter Ablation in Persistent AF (HARTCAP-AF) study, may eventually indicate that the hybrid approach is more effective than stand-alone percutaneous catheter ablation.8 Other evidence gaps relate to the value of opportunistic screening for AF, and AF screening for early detection, as well as how much AF constitutes a mandate for antithrombotic therapy in patients with pacemakers. Prof Crijns also discussed the temporal disconnect between arrhythmia and stroke, the evidence in time-ofcalamity studies, and the correspondence between CHA2DS2-VASC score and use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

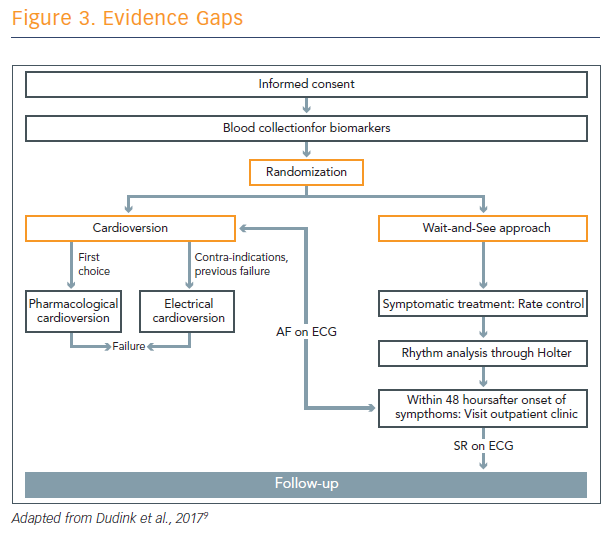

He also described work in progress at Maastricht to compare cardioversion with a ‘wait-and-see’ approach (see Figure 3).9 Prof Crijns thinks that the wait-and-see approach is often successful, because a lot of patients convert without intervention. It gives the clinician time to diagnose these patients.

First-line AF Ablation: Should Be Considered or May Be Considered?

Is first-line ablation of AF a ‘should’ or ‘maybe’ when compared with anti-arrhythmia drugs? According to a 5-year follow-up of first-line ablation patients with a mean of 1.5 procedures and a median of 1 procedure, approximately 80 % will remain in SR.10 This statistic is actually not bad, said Prof Gian-Battista Chierchia of Brussels, Belgium. Ablation is significantly better than antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) in keeping patients who failed an AAD in SR. And, he notes, it is probably age-dependent – the younger, the better.

So why not ablate earlier? Or, alternately, why should ablation occur earlier? There are various reasons. First is safety – ablation is considered less safe than AADs, but in fact higher overall death rates are seen with AADs than in early-ablation patients.11 The second reason is disease progression. If not tackled quickly, paroxysmal AF progresses quickly; in one study, approximately 15 % progressed from paroxysmal to persistent AF within 1 year.12 It has also been shown that ablation tends to delay the progression of the pathology.

“If you ablate, the patients will more likely not progress to persistent AF if they initially presented as paroxysmal AF,” said Prof Chierchia.

Another reason is procedure complexity. The more the pathology advances, the more it tends to be complex to treat the patient.

Trials and literature indicate that ablation is more effective than AADs for extending time to recurrence of symptomatic AF after radiofrequency (RF), and comes with a lower rate of symptomatic AF after RF. Furthermore, the new ESC guidelines state that catheter ablation is the recommended treatment for symptomatic paroxysmal AF, which is refractory to at least one Class I or Class III antiarrhythmic drug.8

The key addition to these guidelines is that patient choice should be fundamental to the decision, provided that it is performed in expert centres, justifying catheter ablation as first-line treatment in selected patients with paroxysmal AF who ask for interventional therapy. The patient should be thoroughly informed about the procedure as part of this component.8