Cardiac arrhythmias during pregnancy pose a serious threat to the health of both mother and foetus. Women with established tachyarrhythmias, congenital heart defects or channelopathies have the highest risk for development of arrhythmias.1,2 They also develop de novo or occur in women without apparent heart diseases. Tachyarrhythmias, including both supraventricular and ventricular tachycardias, are the most common cardiac complications observed during pregnancy. Not only the mother, but also the foetus may develop tachyarrhythmias.3 The exact mechanisms underlying the development of cardiac arrhythmias during pregnancy are unknown, and selection of the appropriate treatment modality is hampered by the lack of randomised studies in pregnant women.1,4,5 This review outlines the current knowledge on the development of tachyarrhythmias during pregnancy, the indications for and considerations of pharmacological treatment and its potential side-effects.

Incidences of Cardiac Arrhythmia During Pregnancy

Maternal Arrhythmias

(Supra)ventricular premature beats are the most frequently observed arrhythmias during pregnancy followed by paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias (SVT); incidences are 33 and 24 per 100,000 pregnancies respectively.6 Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) and atrioventricular reentry tachycardia (AVRT) are the most common supraventricular tachycardias both in pregnant and non-pregnant women with structurally normal hearts and usually do not cause haemodynamic deterioration.7,8 Studies investigating the risk of first onset paroxysmal SVT have shown inconsistent results.7,9–12 Tawam et al.9 described development of de novo paroxysmal SVTs during pregnancy in 13 out of 38 women (34 %).

This is in contrast to a study by Lee et al.7 who reported development of de novo paroxysmal SVT in only 3.9 % of the pregnancies. Recurrences were observed in 55 out of 65 (85 %) pregnant women with a history of paroxysmal SVT.7 In women with congenital heart disease (CHD) arrhythmias, mainly SVT, occurred in 4.5 % and were associated with multiple factors, including the presence of cyanotic heart disease (corrected/uncorrected) and usage of cardiac medication prior to gestation.1,13 Focal atrial tachycardia (FAT) occurs rarely during pregnancy and has mainly been described in case reports.14–19 Atrial fibrillation (AF) or atrial flutter (AFL) develop infrequently during pregnancy; a combined incidence of 2 per 100,000 pregnancies has been reported.6 In patients with known AF/AFL, a recurrence rate of 52 % has been described.20

The overall incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VT) or fibrillation (VF) in pregnant women is also very low (2 per 100,000 pregnancies).6 In women with structurally normal hearts monomorphic VT may develop during pregnancy, for example as a result of coronary artery disease or left ventricular dysfunction.21,22 VTs occur more often in patients with underlying acquired (coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy) or inherited (CHD or channelopathies) heart disease. VT recurrences have been described in 27 % of women with heart disease and VT episodes prior to pregnancy.20

Foetal Arrhythmias

Foetal tachyarrhythmias occur in approximately 2 % of pregnancies. Most arrhythmias are paroxysmal SVT (73 %) or AFL (26 %).23,24 VTs have been described in a review by Krapp et al.23 in 3 out of 485 cases (0.6 %) and may be associated with myocarditis, total atrioventricular block or congenital long QT syndrome.25

Haemodynamic Alterations During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the cardiovascular system is faced with significant changes which can precipitate the occurrence of arrhythmias. First, the blood volume increases by 35–40 % and is accompanied by an increase in heart rate and simultaneous decrease in vascular resistance. This leads to an increase in cardiac output of 30–50 %, already starting within the first weeks of pregnancy and with the largest increase occuring in the first 16 weeks.26–30 The increased blood volume has a physiological structural impact on the heart. The ventricles and atria dilate and the left ventricular mass increases during pregnancy.27,31 These effects are even greater in twin/multiple pregnancies.27,32 Mechanical stretch can facilitate arrhythmias by depolarisation of the membrane potential, premature depolarisations and dispersion in refractoriness.33,34 Furthermore, the increase in heart rate during pregnancy may act as a trigger in susceptible patients.35 There are also indications that oestrogen and progesterone may contribute to altered cardiac repolarisation facilitating arrhythmias.36

Besides the hyperdynamic state and altered hormonal status possibly predisposing pregnant women to arrhythmias, the high incidence of arrhythmias in patients with pre-existent heart disease or previous arrhythmic episodes indicates that this is probably the most important risk factor for arrhythmias in pregnancy.20

Indications and Considerations for Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy during Pregnancy

The goal of anti-arrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy in general is to reduce ectopic activity or to modify critically impaired conduction. The ideal AAD has a greater effect on the arrhythmogenic substrate than on normal depolarising tissues, decreases mortality and has no sideeffects. However, many of the currently available AADs have proarrhythmogenic effects and could even increase mortality.4

Pharmacological therapy of a pregnant woman is imperative in case of haemodynamic instability and/or diminished placentouterine blood flow. The main issue of pharmacological treatment of tachyarrhythmias during gestation is the potential teratogenic effect on the foetus as most AADs cross the placental barrier. Maintenance of adequate therapeutic drug levels in pregnant women is challenged by an increased intravascular volume, reduction of plasma proteins concentrations, increased renal blood flow and hepatic metabolism. Gastrointestinal absorption is also altered by changes in gastric secretion and intestinal motility.37,38 Foetal tachyarrhythmias should be treated when there is a risk of developing foetal heart failure. Subsequently, hydrops fetalis may develop and premature delivery or foetal death may occur.39,40

Effects and Safety of Anti-arrhythmic Drugs

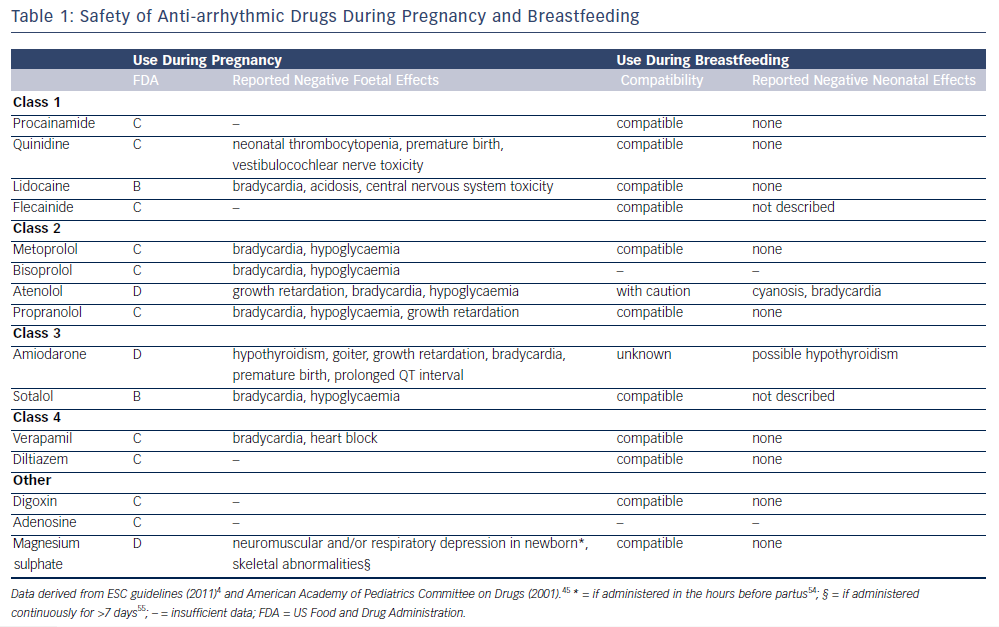

There are very limited data available for the effects and safety of AAD therapy in pregnancy. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has classified drugs into five categories (A–D and X) to indicate the supposed effects and level of evidence. In categories A and B studies did not show any foetal toxic effects, where in category B the evidence is only from animal studies. In category C there have been adverse foetal effects demonstrated in animal studies, and in category D adverse foetal effects have been reported in human studies. However, for all these categories potential benefits may outweigh the risks and the drug may therefore be administrated if the situation requires it. Only in category X is the drug clearly contraindicated due to substantial evidence for adverse foetal effects. Here the risks do not outweigh the possible benefits. However, it is important to keep in mind that this system is a simplified classification and detailed drug information should be used when determining the potential safety in individual patients. Table 1 demonstrates that for most AADs some negative foetal effects have been reported in animal studies (category C), the most safe AADs appear to be lidocaine and sotalol and most adverse foetal effects during pregnancy have been reported with amiodarone and atenolol. The negative foetal effects of AADs that have been reported are also summarised in Table 1.4,41–44 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has classified most AADs as compatible with breastfeeding; only atenolol and amiodarone are possibly less favourable to use during the lactation period.45 AADs during pregnancy have been more extensively investigated for the treatment of foetal arrhythmias. The AADs recommended for foetal arrhythmias include sotalol and digoxin.46

Drug Therapy

Supraventricular Tachycardia

If immediate conversion of AVNRT or AVRT is required and the vagal manoeuvre is unsuccessful, administration of adenosine IV is recommended.3,4 This terminates approximately 90 % of the AV(N) RTs;47 an alternative is IV metoprolol.3 If long-term treatment for AVNRT is required, digitalis or metoprolol are the first-line drugs.3 Electrical or pharmacological cardioversion for FAT, although often successful, is discouraged due to the relatively high risk of recurrences and is only indicated in case of haemodynamic instability. Administration of adenosine may successfully terminate FAT in 30 %.4 Rate control in FAT is indicated for the prevention of tachycardiomyopathy and can be achieved with the use of digitalis or metoprolol.3,4 Flecainide or propafenone could be considered for rhythm control therapy. Use of the lowest effective dose of amiodarone should only be considered when the FAT results in haemodynamic instability, it is refractory to all other AADs and conversion to sinus rhythm is required.4

In case of AF or AFL requiring conversion to sinus rhythm, the use of ibutilide or flecainide is effective and recommended for non-pregnant patients,48,49 however experience of these drugs during pregnancy is limited.3,4 In pregnant women with an AF or AFL episode with a duration longer than 48 hours that requires direct current cardioversion, the use of oral anticoagulants at least three weeks before cardioversion is necessary.4 Atrial stunning after cardioversion increases the risk of thromboembolic events, and it is therefore recommended that oral anticoagulants are continued for at least four weeks.4 Oral anticoagulants should be replaced by low molecular weight heparin in the first and third trimester of pregnancy because of the potential negative effects on the foetus. Metoprolol is the drug of first choice to control ventricular heart rate. Verapamil is the drug of second choice since the blood levels of digoxin during pregnancy are unreliable. Propafenone or flecainide in conjunction with AV nodal blocking agents or sotalol can be used when other rate control strategies fail.3,4,48,49

Ventricular Tachycardia

Acute treatment of ventricular tachycardia (VT) is indicated in all patients and can be achieved by electrical (first choice) or pharmacological cardioversion.4 Amiodarone IV should only be used if VT persists, or when the VT is refractory to electrical cardioversion, drug resistant and haemodynamically comprising. Patients with structurally normal hearts or congenital long QT syndrome should be treated with b-blockers as a prophylaxis for development of VT recurrences. Verapamil could also be considered in patients without structural heart disease.3,4

Foetal Arrhythmias

As mentioned above, persistence of foetal arrhythmias predisposes for development of hydrops fetalis, ventricular dysfunction or eventually death.4 Hence, treatment of persistent foetal arrhythmias is indicated. Pharmacological treatment of primary foetal arrhythmias includes digoxin as the first choice.46 If unsuccessful, sotalol and verapamil, procainamide or quinidine can be administered. Sodium and potassium channel blockers have been safely applied during foetal ventricular arrhythmias.50,51 If maternal, transplacental treatment is not successful, umbilical or intraperitoneal52 drug administration or direct foetal intramuscular injection53 of anti-arrhythmic agents have been described. However, this approach has not (yet) been incorporated in the European or American Guidelines.

Conclusion

Prescription of anti-arrhythmic drug therapy in pregnant women is challenging due to the potential severe side-effects in both the mother and foetus. In addition, there are no major studies guiding selection of the safest and most effective anti-arrhythmic drug. Hence, initiation of anti-arrhythmic drug therapy requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits to the individual patient.

Clinical Perspective

- Initiation of anti-arrhythmic drug therapy requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits to the individual patient.

- Pharmacological therapy of a pregnant woman is required in cases of haemodynamic instability and/or diminished placento-uterine blood flow.

- However, the use of AADs during pregnancy should be avoided whenever possible.