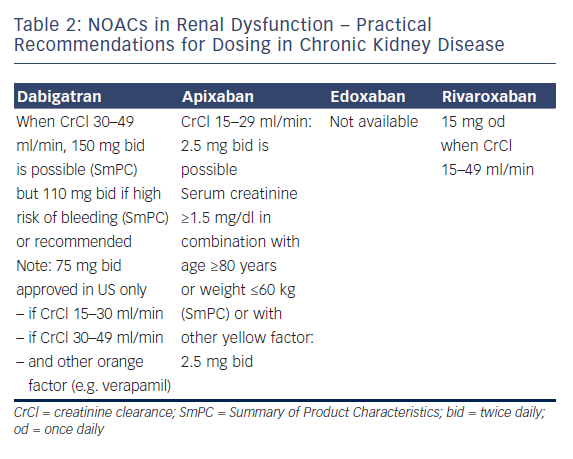

Professor Le Heuzey started by describing the absorption and metabolism of NOACs. All NOACs are partially eliminated by the kidneys. The renal elimination of NOACs varies considerably: dabigatran 80%, apixaban 25 %, rivaroxaban 35 % and edoxaban 50 %, and therefore different NOACs have different levels of contraindications.42 Practical recommendations have been proposed for the use of NOACs in chronic kidney disease (see Table 2); dabigatran is contraindicated if creatinine clearance (CrCl) is lower than 30 ml/min, apixaban and rivaroxaban if lower than 15 ml/min (no data available for edoxaban at time of recording).1,2 Bioavailability also differs according to the drug: for dabigatran, 3–7 %; for edoxaban 50 %, for edoxaban 62 %, and for rivaroxaban 66–100 %. Therefore, different dosages are recommended in suboptimal renal function. The age of the patient should also be taken into account because elderly patients often have decreased renal clearance.

Guidance is also available regarding when to stop NOACs before a planned surgical intervention. The duration of action of the drug is directly related to CrCl: with a normal renal clearance NOACs can be stopped 24–48 hours before a planned surgical intervention, but for example with a CrCl of 30-50 ml/min, the effect of dabigatran can persist for up to 96 h. The risk of bleeding associated with the intervention should of course also be taken into account. The proposal of EHRA is that renal function should be monitored regularly in patients taking NOACs and the dose adapted accordingly. Renal function should be monitored at the following intervals in patients with chronic kidney disease: yearly with a CrCl ≥60 ml/min; 6-monthly for elderly (>75 years) or frail patients on dabigatran (CrCl 30–60 ml/min); and 3 monthly when CrCl ≤30 ml/min.

In the panel discussion, Professor De Caterina considered that NOAC therapy should not be used in patients with CrCl ≤30 ml/min. A traffic light analogy was suggested for advising doctors, with a red light at CrCl ≤30 ml/min, yellow at 30–50 ml/min and green ≥ 50 ml/min. However, following the availability of drugs with lower renal clearance, this might change in the future, especially if dosages are carefully tailored to the individual.

At adjusted dosages, the NOACs have shown preserved efficacy in patients with impaired renal function, whereas there is little evidence for the efficacy of warfarin in these patients. The choice of drug should be influenced by renal function; while some panel members still prescribe warfarin to patients with CrCl 30–50 ml/min, all concede that NOACs might be preferable. Regular CrCl monitoring is essential. The panellists consider that ‘NOAC outpatient-clinics’ in some countries are well equipped to handle the treatment decisions, follow-up and paperwork involved with prescribing NOACs, not only in patients with renal impairment. Despite these restrictions, in most phase III trials, patients with renal impairment derived considerable benefit from NOACs. In conclusion, as far as renal function is concerned with regards to NOACs, renal function must be known before choosing a drug, before choosing the dose, in follow-up because renal function will change, and when planning, e.g. a surgical intervention. Renal function is important with regards to patients taking NOACs.